Human beings change spontaneously when the discomfort of being in a certain situation seems greater than the change. However, some changes can be very difficult for humans to process and put us in a state of mourning.

Organizational Anticipatory Mourning and Its Effects on the Workforce

Grief is a necessary state of transition for people to process the losses, experience feelings such as anxiety, immobilization, denial, fear, anger, bargaining, guilt, depression, and finally, work on the resignification of, and stabilization in, a new adapted state.

When we know in advance that we will experience a change that will be perceived as a loss, we go into a state of anticipatory grief. This is a common phenomenon in human behavior when we feel a major change we can experience in life—death of a loved one or our own—is imminent. This was first described by doctors who noted that the wives of soldiers sent to war went into a state of mourning even before their death was confirmed.

Within hospital psychology, anticipatory grief, if properly dealt with, can be positive for people to process impending losses, preparing patients and their families for an irreversible situation. Patients are able to do things they would like to have done but had not had a chance to do. Friends and family can resolve outstanding conflicts, thus minimizing the effect of guilt in the mourning phase that follows the fatal outcome.

Anticipatory grief can also be found in many organizations when a change is about to happen. If the change has not been adequately communicated or understood, its effect will be negative, creating a feeling of anxiety and fear fueled by uncertainty about the future.

Often this change does not even exist. It is the result of a myth or an organizational environment of low trust in the leaders and organization. The effects of organizational anticipatory grief, in this case, are very serious. People come to a standstill, becoming angry and even aggressive. Surviving, maintaining the status quo, is more important than anything else. Productivity is affected. Creativity gives way to stagnation. Corridors and common areas such as cafeterias and break rooms become information points. Truths are created or distorted, creating an atmosphere of pessimism toward the future. Knowledge is no longer shared by the workforce and is now used as a strategy in an alleged dispute over the maintenance of personal positions in the organizational structure. When the change occurs, resistance has already been magnified by the general state of early suffering promoted by lack of timely communication or even inadequate initial communication of the changes that were to come.

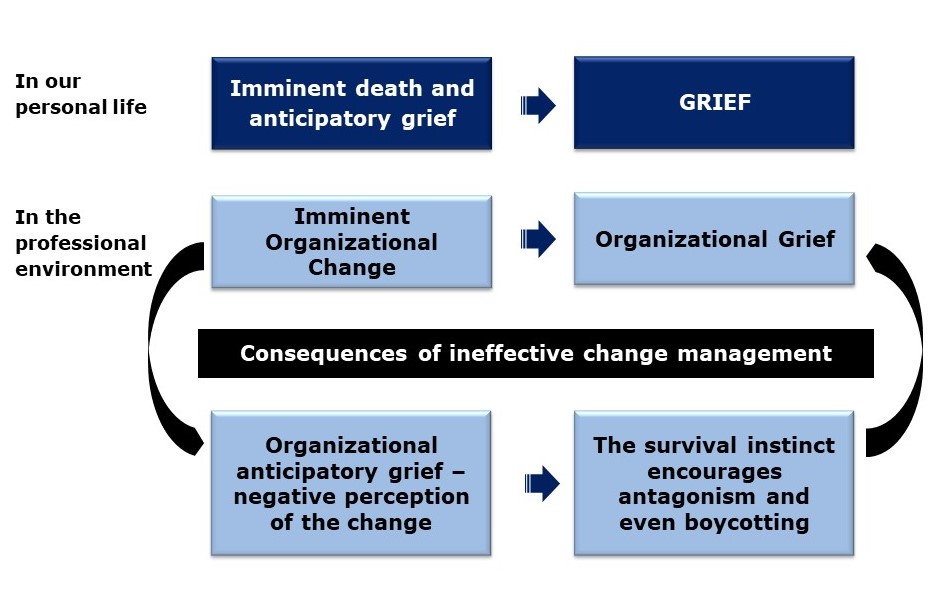

The following figure compares human relations at the personal and professional levels. In this case, the behavior at the professional level reflects a situation where changes were not managed or where changes and their results were managed ineffectively.

Figure 1 – Repercussions of Change without Effective Management

Source: HCMBOK® – The Human Change Management Body of Knowledge.

Leading change by adopting a set of best practices can avoid or greatly minimize the negative effects of organizational anticipatory mourning. When these best practices are appropriately applied at the right time, they generate psychological security, reduce negative impacts on the organizational climate, minimize antagonisms, and expand resilience, preparing the organization for better acceptance of changes. Note that resilience is not impermeability. Resilience means being affected by change but having the capacity to adapt and return to a state adjusted to a new reality.

When the organizational anticipatory grief is well managed, as in hospital psychology, many actions can be implemented to channel negative perceptions of change to a more positive situation through better opportunities for processing losses and adjusting behaviors as necessary to adapt to the future situation. We thus leave a situation where what we feel (uncontrollable instance) is dominant and gradually replace what we feel with how we act, how we manage our attitudes before the change (controllable instance).

Even when we cannot choose the circumstances we will experience, we can always choose how we will experience them.

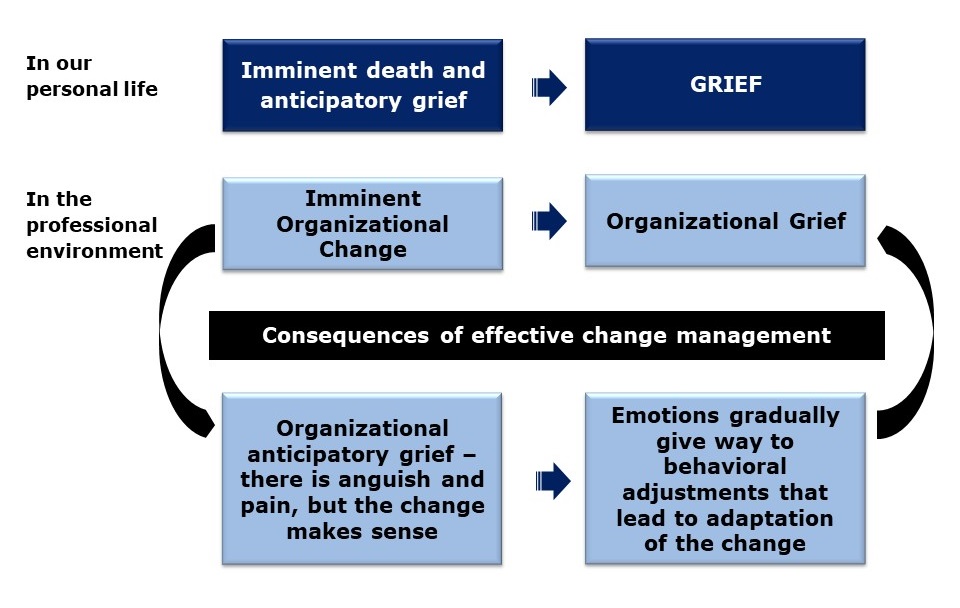

Understanding the need for an organizational change does not necessarily eliminate the pain that the change will cause, but for many it makes the situation more transparent, gives meaning to things, eliminates distorted perceptions of reality, and accelerates the process of adjustment to the future state of the organization. The following figure compares the changes at the personal and professional levels. This time the comparison reflects the deployment of effective change management.

Figure 2 – Repercussions of Change with Effective Management

Source: HCMBOK® – The Human Change Management Body of Knowledge.

Human Barriers to Change

Changing isn’t easy for most people. Some are naturally more adaptable and go through the change journey with less distress. Others may need more time to transition between the old and the new way of working.

However, even a person who adapts more easily to a particular change process may not adapt with the same ease to a different transformation scenario. Each change scenario is unique and affects a human being differently.

There are various factors influencing the human change process. This is an extremely complex subject involving areas like neuroscience, psychology, anthropology, etc. Here, we’ll focus on the human barriers that most influence the organizational change process.

The perception of loss comes before perceiving the benefits of change.

Changes, in general, bring some discomfort and often the perception of loss. The most common human response is to perceive everything we will lose before valuing the benefits of the change.

The role of leaders in organizational changes is essential for the success of the endeavor. Every change requires leadership and management, which, in turn, require technical skills and sensitivity to human factors.

Change leaders need to understand that change isn’t an event but rather a journey, a process that isn’t always simple for humans.

Even if we perceive various benefits and can understand that change is necessary, the change cycle will likely go through various phases.

According to Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1969), when facing what might be the most complex change in our lives—living with death—we go through various stages such as denial, anger, bargaining, and depression. These are phases that take time to assimilate until we reach the acceptance phase.

Human changes in the organizational environment present similar phases and require patience for people to find new meaning for their professional lives within the introduced changes.

No one has the power to change another, but we all have the responsibility to create a healthy environment for the change journey to be less painful and occur in the shortest possible time.

Several best practices for leading organizational changes, which we’ll discuss in the following chapters, form this favorable framework for the change process.

Human behavior is complex, and each of us brings our own peculiarities. What is simple and obvious for you may not be so for another person. For example, understanding what someone who has lachanophobia (a phobia, aversion, or irrational fear of vegetables) feels when facing a green salad.

Empathy is the most important skill for change leaders.

When we talk about empathy, we go beyond the ability to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. The pain of change belongs to the other, and we cannot feel it. We cannot replicate the feelings and emotions each individual experiences. In this case, empathy means an unconditional respect for someone’s difficulty in dealing with changes.

In the realm of organizational changes, it’s possible that some people exhibit antagonistic behavior while others show high engagement. Each case is unique, and every human being has their own paradigms and individual perceptions.

Leaders have the role of understanding and valuing the human factor as the central point for successful changes. Inspiring, exciting, motivating, and sharing the vision are attitudes that are part of the leader’s role in organizational changes.

It’s the responsibility of true leaders to create a healthy environment for people to self-manage their emotions and behaviors and, ultimately, go through the change journey. After all, organizational changes only solidify when accompanied by human changes.

Being human is being complex.

We are logical beings, but above all, psychological beings. We have a hidden and unconscious side that influences our actions and attitudes. Even those who develop profound self-awareness may be surprised by their own behavior in the face of stress and destabilization caused by a change in the organization.

Assuming that creating awareness and understanding of change, developing a sense of urgency, empowering, celebrating, recognizing, etc., is enough to generate engagement, is treating the human being merely as a logical entity. The human being is much more complex than that, and engagement is much more connected to the emotional than the rational instance.

Intelligent strategies for emotional persuasion can be highly effective and should be intensively applied. Let’s say there is a large lawn in a park that is often trampled by people. What do you think would work better to solve this problem:

- putting up a sign saying “DO NOT STEP ON THE GRASS” or

- putting up a sign saying “Hello, I am the grass, if you don’t want to hurt me, please don’t step on me”?

The culture of each region can influence human responses. After all, we all undergo the phenomenon of social influence, the natural pressure of accepted or unaccepted behaviors by society. However, the second option will likely be the most successful because it touches on people’s emotions rather than reason.

Fear and psychological insecurity are frequent barriers to organizational change. The best approach to reducing the effects of these barriers is transparent communication, widespread dissemination of the vision of the organization’s future state, the purpose of change, and active sponsorship. The leader must exercise their social influence as an authoritative and referential figure, inspiring and motivating people to trust in the benefits brought by the changes.

We must also remember that we all suffer from the influence of the ego (in terms of arrogance, vanity, haughtiness, pride, and individualism), perception of change in relation to status and power, and finally, personal agendas. As human beings, status and power are things we frequently seek as a natural need for social recognition. In the organizational context, these factors are even more relevant as they will have a direct impact on employees’ careers and remuneration.

Understanding these human barriers to change allows us to devise strategies to reduce antagonism and increase engagement in the intended changes.

Did you like this article? We recommend reading the article below:

About HUCMI and HCMBOK Training and Certification Program:

Want to learn more about HUCMI’s international training and certification programs? Visit us on: https://hucmi.com/TreinamentoeCertificacao.aspx

Follow us on social networks and stay connected in everything the most modern and innovative that happens in the universe of organizational change management: https://linktr.ee/hucmi